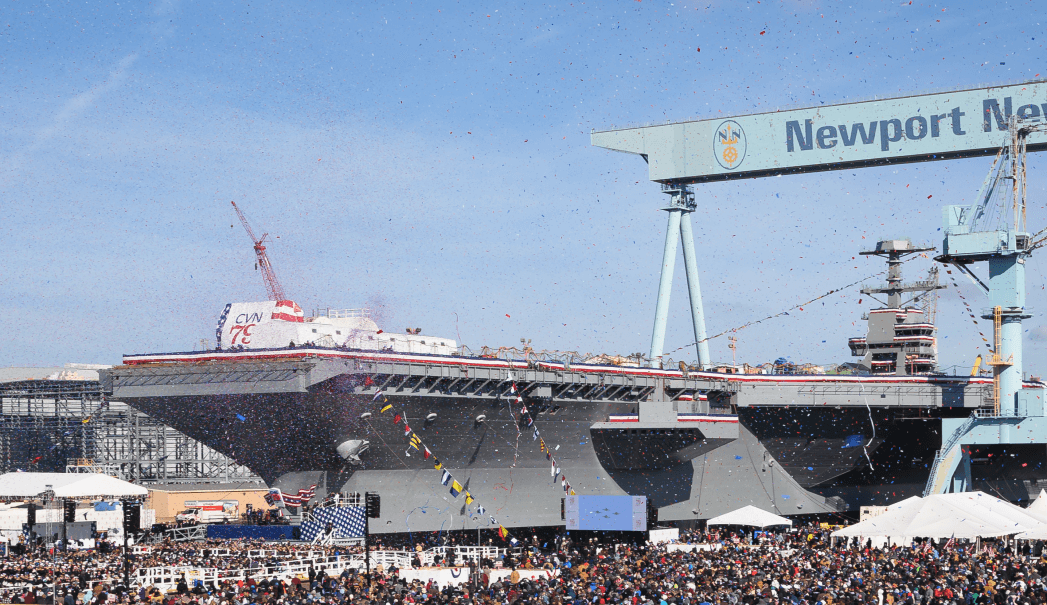

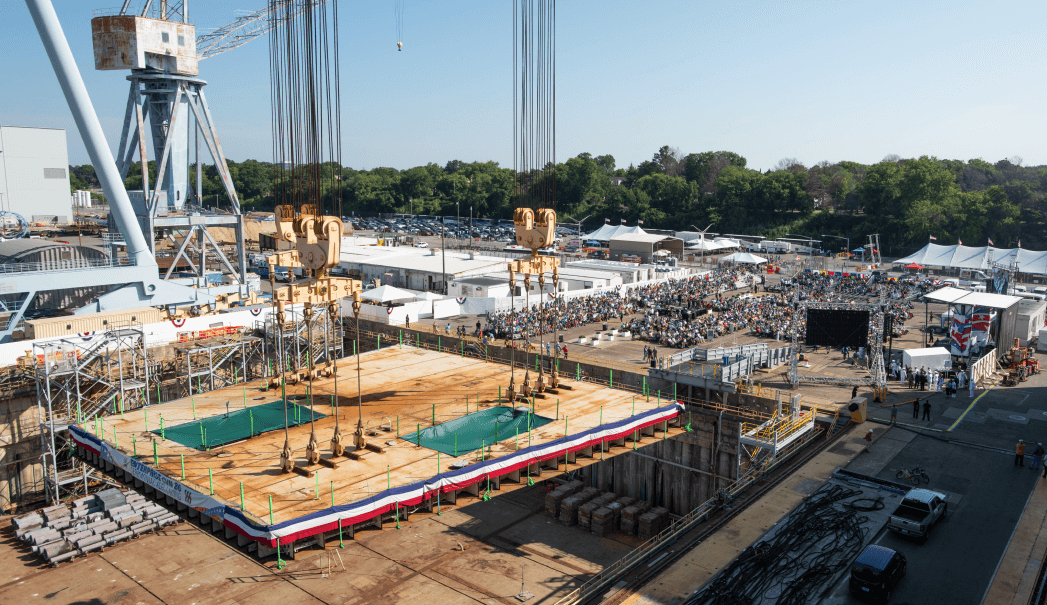

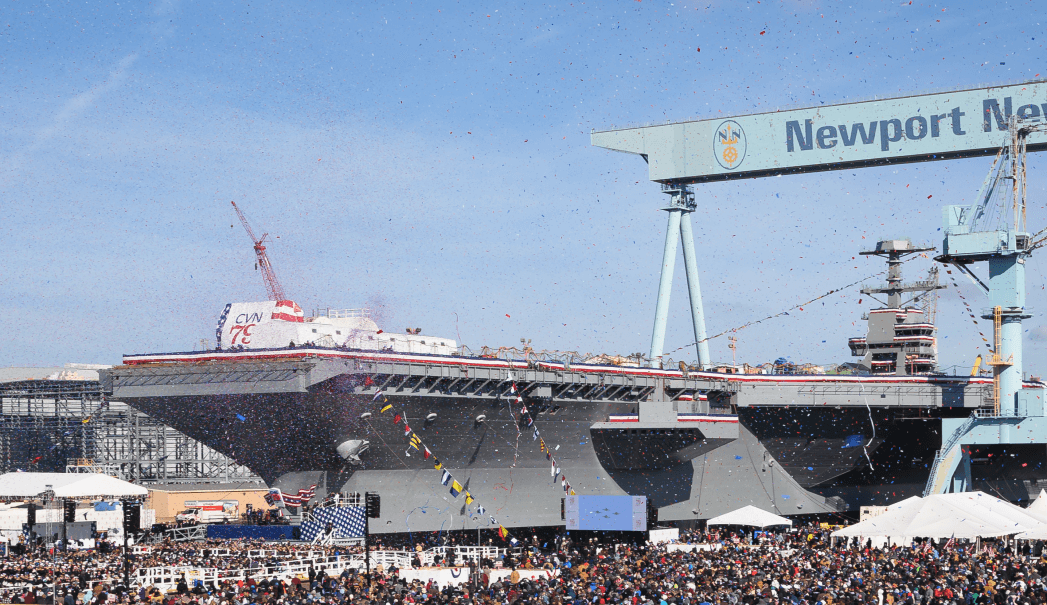

Newport News Shipbuilding is currently building the Gerald R. Ford – class, the first new design for an aircraft carrier in decades.

Newport News Shipbuilding is currently building the Gerald R. Ford – class, the first new design for an aircraft carrier in decades.

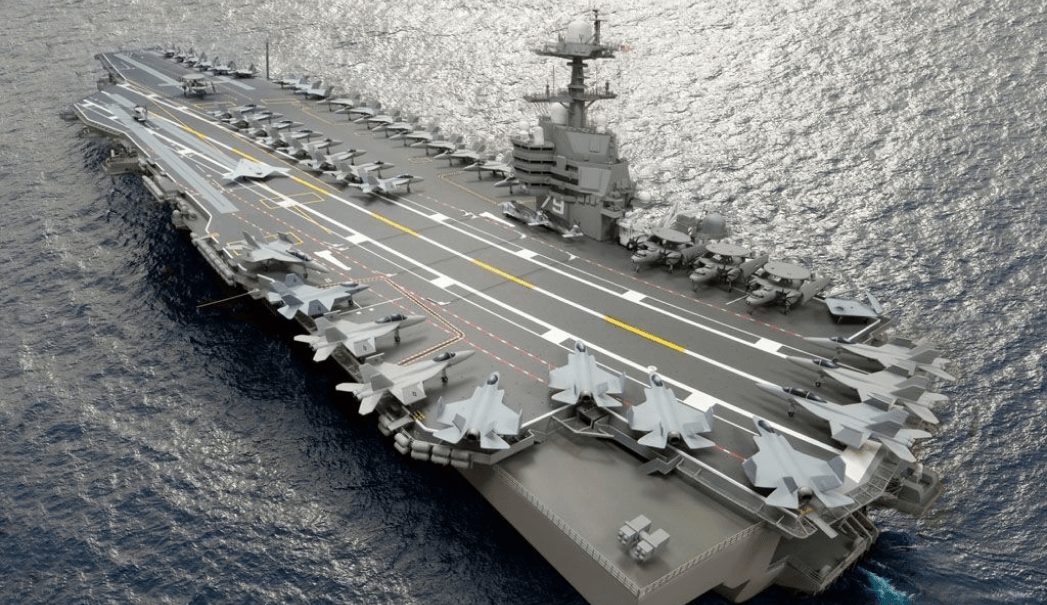

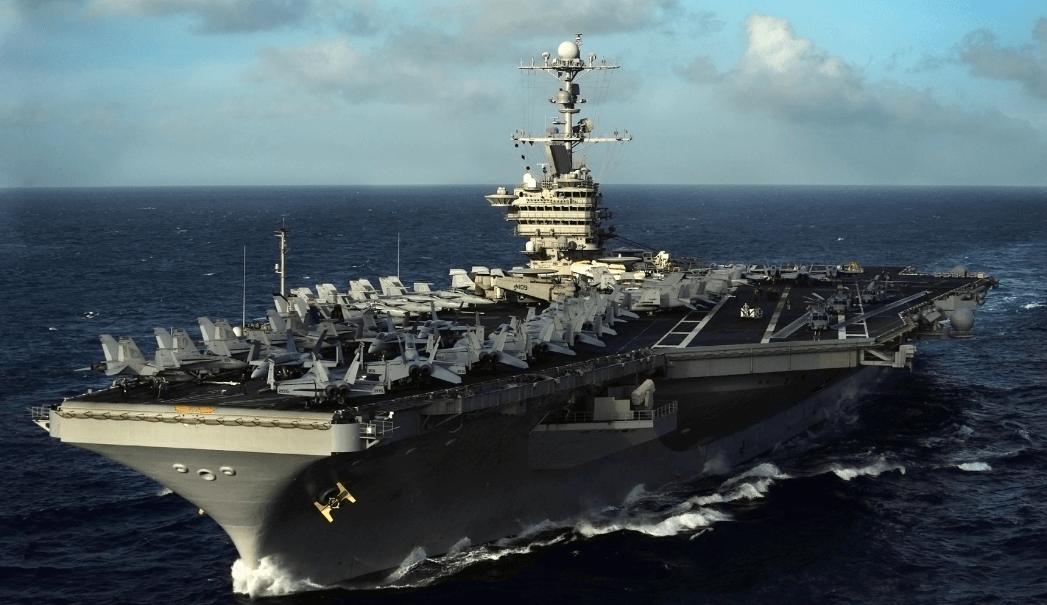

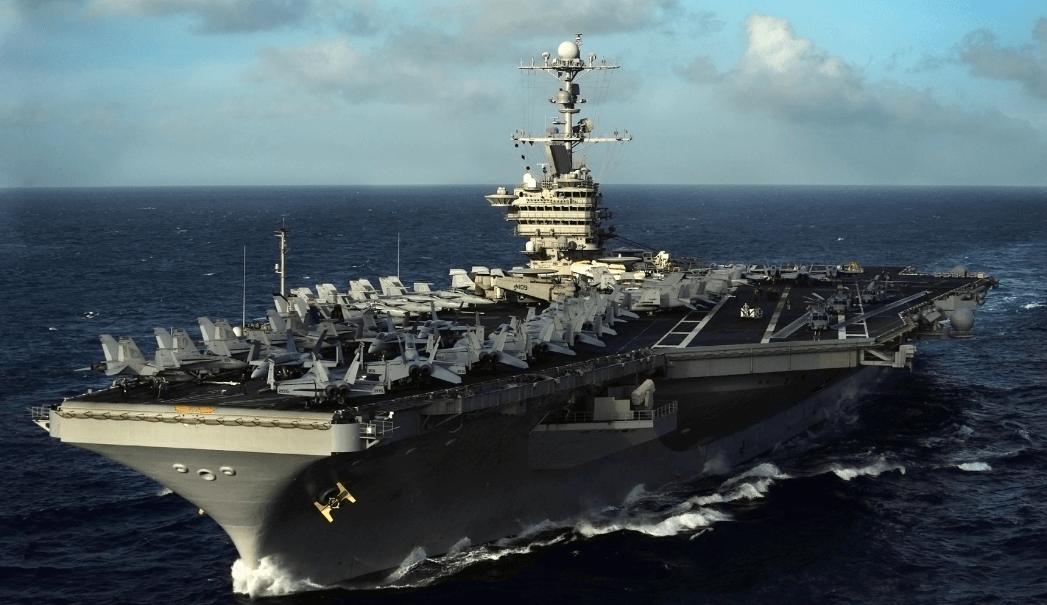

Nuclear-powered aircraft carriers are one of the most complex machines ever made by man. The warfighting components of launching and retrieving jet aircraft make it complicated enough, but beneath the surface is a bustling city with two power plants, food services, medical facilities, waste management systems, and even desalination plants that convert sea water to fresh water.

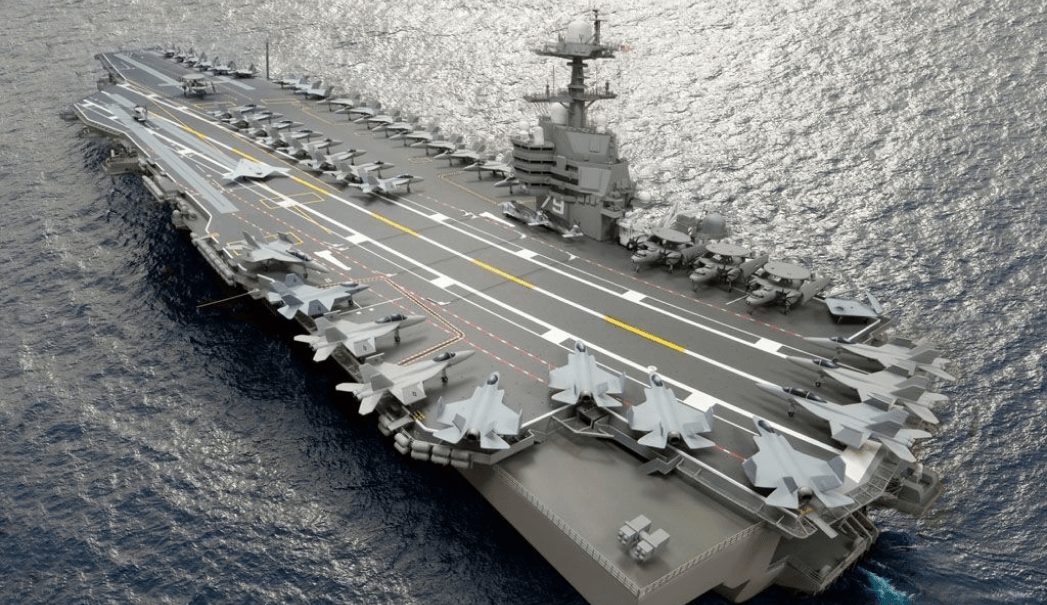

The shipbuilders at Newport News Shipbuilding who build these floating warfighters are now building the newest class of aircraft carriers, the Gerald R. Ford-class. With new software-controlled electromagnetic catapults and weapons elevators, a redesigned flight deck and island, and more than twice the electrical capacity of the preceding class, these aircraft carriers are truly designed for the 21st century and beyond.

The Ford-class is the first new design for a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier since Nimitz (CVN 68). During the design process, the shipbuilders found hidden value in every square inch of the ship, saving the Navy a projected $4 billion in ownership costs over the ship’s 50-year lifespan.

We service aircraft carriers throughout their lifetime, including the mid-life project that refuels the nuclear reactors (RCOH), and inactivation.

Newport News Shipbuilding is the only shipyard to perform refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) work on aircraft carriers. This massive undertaking was described in a 2002 Rand Study as one of the most challenging engineering and industrial tasks undertaken anywhere by any organization.

The multi-year project is performed only once during a carrier’s 50-year life and includes refueling of the ship’s two nuclear reactors, as well as significant repair, upgrade and modernization work. We have completed the refueling and complex overhaul of the first six ships of the Nimitz-class, USS Nimitz (CVN 68), USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69), USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71), USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) and USS George Washington (CVN 73). Today, we are performing this work on the seventh ship in the class, USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74).

Newport News Shipbuilding also offers inactivation services for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. In 2018, NNS successfully completed the inactivation of Enterprise (CVN 65), which began in 2013. The NNS-built Enterprise was the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and the only ship of its class.

Service of each aircraft carrier does not end after delivering it to the Navy. We service the ships through their lifetime, around the world.

Our portfolio of in-service aircraft carrier fleet service offerings includes maintenance and modernization work on aircraft carriers at our facilities. We also provide technical and life cycle logistics services wherever the need is around the world.

Newport News Shipbuilding also offers inactivation services for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. In 2018, NNS successfully completed the inactivation of Enterprise (CVN 65), which began in 2013. The NNS-built Enterprise was the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and the only ship of its class.

Since the construction of Ranger (CV 4) in the 1930s, HII’s Newport News Shipbuilding division has proudly been building U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. The 1960s ushered in the start of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier era, and since then, NNS has been the sole designer and builder of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers for the U.S. Navy. Starting with Enterprise (CVN 65), we have created these nuclear-powered marvels of naval engineering from initial design to delivery.

Working closely with the Navy, we design and engineer aircraft carriers to their specifications and needs, adding new technologies and innovations with each new ship we build, refining the process each step of the way. The design and engineering of these ships are unparalleled in the world shipbuilding, with our carriers lasting 50 years in often extreme conditions.

Nuclear propulsion gives these ships the ability to go for years without refueling, adding unique strategic advantages to the Navy. In partnership with the Navy’s nuclear program, we continually improve the quality and safety of the nuclear reactors that power the ships while increasing the energy efficiency.

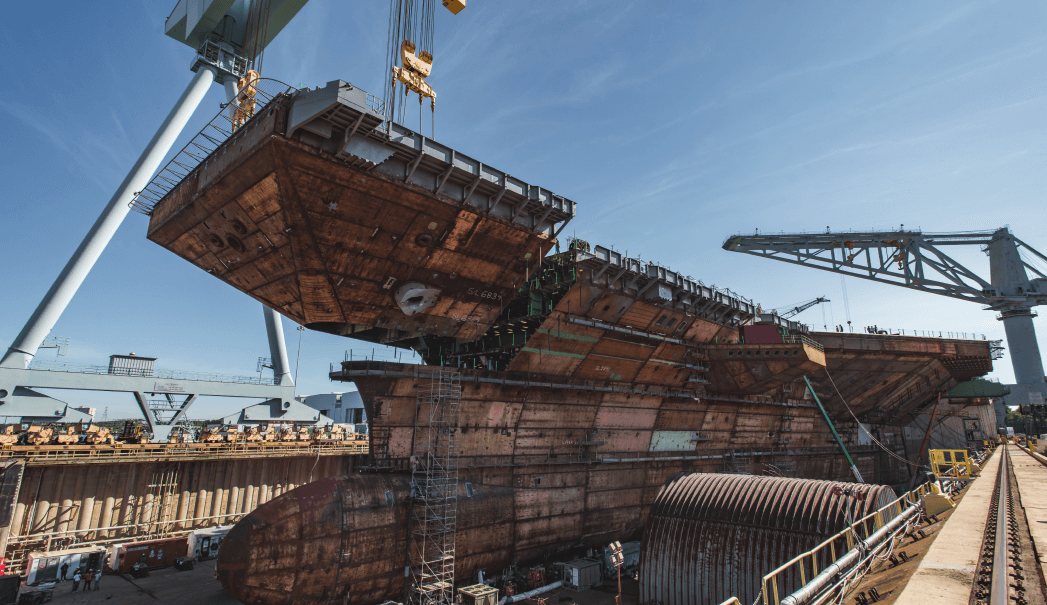

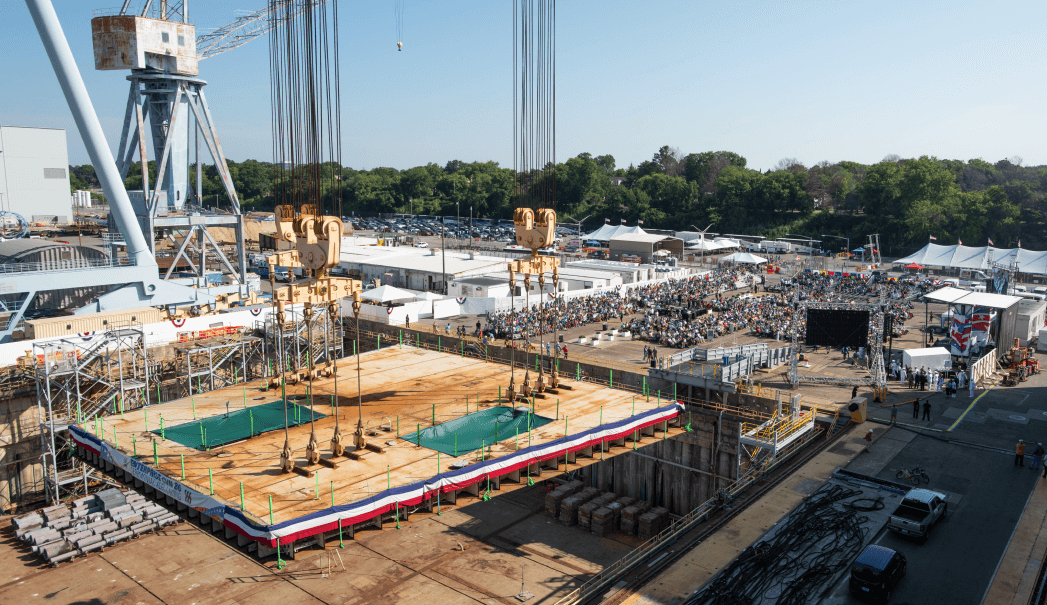

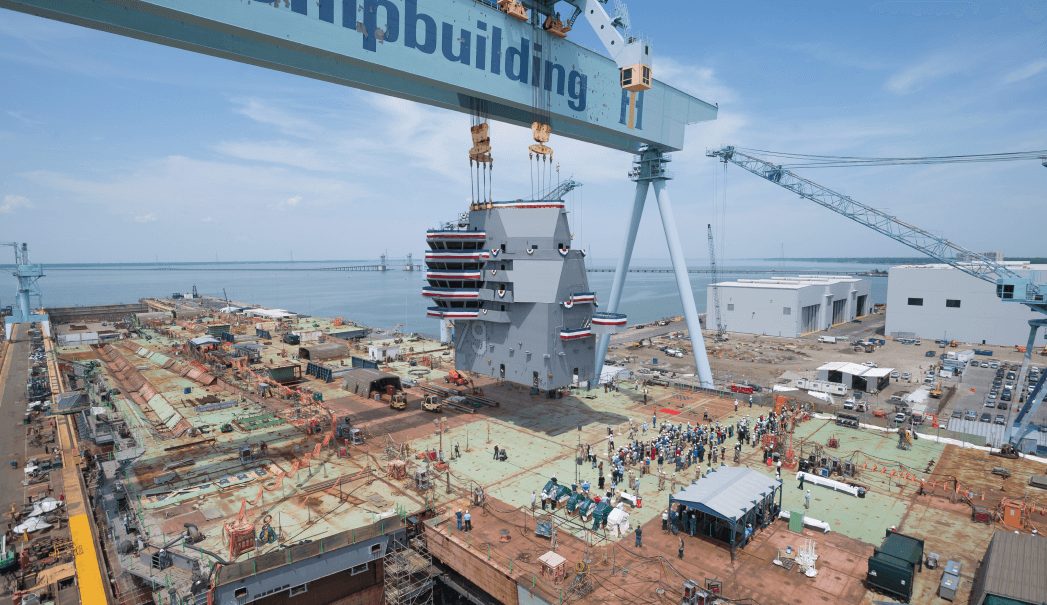

Building a carrier is a major construction undertaking. Their size is enormous: if stood up, a Nimitz-class carrier is almost as tall as the Empire State Building. Aircraft carriers must support thousands of sailors, aircraft and enough supplies to maintain both for months. The construction process requires large amounts of material ordered years in advance and the coordination of thousands of skilled craftsmen.

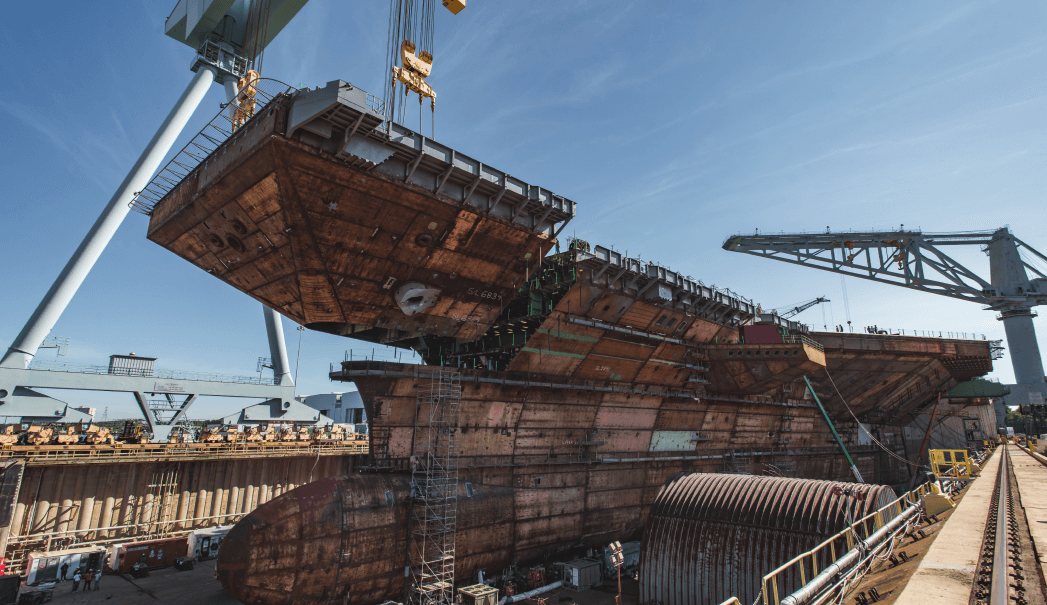

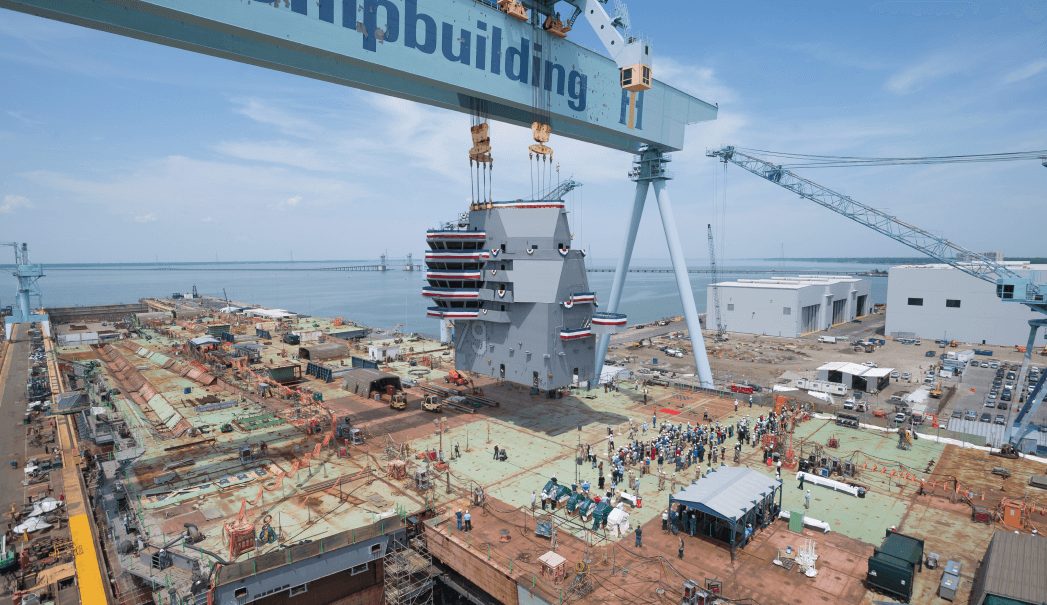

In the past, most ships were built from the bottom up in a single location. Today, shipbuilding is primarily ‘modular,’ which means that large parts of the ship are completed before being added to the ship using a “superlift.” This approach requires a large crane and dry dock; we have the largest dry dock and gantry crane in the United States. At the 25-year half-life of a carrier, we also perform what is called Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH), which includes refueling of the ship’s nuclear reactors, as well as significant repair, upgrades and modernization work.

Newport News Shipbuilding is the only shipyard to perform refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) work on aircraft carriers. This massive undertaking was described in a 2002 Rand Study as one of the most challenging engineering and industrial tasks undertaken anywhere by any organization.

The multi-year project is performed only once during a carrier’s 50-year life and includes refueling of the ship’s two nuclear reactors, as well as significant repair, upgrade and modernization work. We have completed the refueling and complex overhaul of the first five ships of the Nimitz-class, USS Nimitz (CVN 68), USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69), USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) and USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72). Today, we are performing this work on the sixth and seventh ships in the class, USS George Washington (CVN 73) and USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74).

Newport News Shipbuilding also offers inactivation services for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. In 2018, NNS successfully completed the inactivation of Enterprise (CVN 65), which began in 2013. The NNS-built Enterprise was the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and the only ship of its class.

Since the construction of Ranger (CV 4) in the 1930s, HII’s Newport News Shipbuilding division has proudly been building U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. The 1960s ushered in the start of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier era, and since then, NNS has been the sole designer and builder of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers for the U.S. Navy. Starting with Enterprise (CVN 65), we have created these nuclear-powered marvels of naval engineering from initial design to delivery.

Working closely with the Navy, we design and engineer aircraft carriers to their specifications and needs, adding new technologies and innovations with each new ship we build, refining the process each step of the way. The design and engineering of these ships are unparalleled in the world shipbuilding, with our carriers lasting 50 years in often extreme conditions.

Nuclear propulsion gives these ships the ability to go for years without refueling, adding unique strategic advantages to the Navy. In partnership with the Navy’s nuclear program, we continually improve the quality and safety of the nuclear reactors that power the ships while increasing the energy efficiency.

Building a carrier is a major construction undertaking. Their size is enormous: if stood up, a Nimitz-class carrier is almost as tall as the Empire State Building. Aircraft carriers must support thousands of sailors, aircraft and enough supplies to maintain both for months. The construction process requires large amounts of material ordered years in advance and the coordination of thousands of skilled craftsmen.

In the past, most ships were built from the bottom up in a single location. Today, shipbuilding is primarily ‘modular,’ which means that large parts of the ship are completed before being added to the ship using a “superlift.” This approach requires a large crane and dry dock; we have the largest dry dock and gantry crane in the United States. At the 25-year half-life of a carrier, we also perform what is called Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH), which includes refueling of the ship’s nuclear reactors, as well as significant repair, upgrades and modernization work.

Newport News Shipbuilding is the only shipyard to perform refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) work on aircraft carriers. This massive undertaking was described in a 2002 Rand Study as one of the most challenging engineering and industrial tasks undertaken anywhere by any organization.

The multi-year project is performed only once during a carrier’s 50-year life and includes refueling of the ship’s two nuclear reactors, as well as significant repair, upgrade and modernization work. We have completed the refueling and complex overhaul of the first five ships of the Nimitz-class, USS Nimitz (CVN 68), USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69), USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) and USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72). Today, we are performing this work on the sixth and seventh ships in the class, USS George Washington (CVN 73) and USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74).

Newport News Shipbuilding also offers inactivation services for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. In 2018, NNS successfully completed the inactivation of Enterprise (CVN 65), which began in 2013. The NNS-built Enterprise was the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and the only ship of its class.

4101 Washington Ave.

Newport News, VA 23607

4101 Washington Ave

Newport News, VA 23607

1000 Jerry St. Pe’ Highway

Pascagoula, MS 39568

8350 Broad Street, Suite 1400

McLean, VA 22102

2451 Crystal Drive, Suite 1100

Arlington, VA 22202